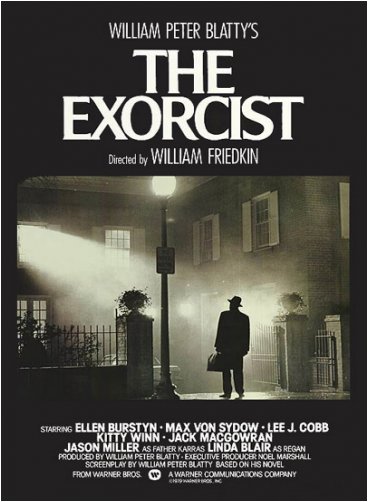

The Exorcist

When a teenage girl is possessed by a mysterious entity, her mother seeks the help of two priests to save her daughter.

The year 1973 began and ended with cries of pain. It began with Ingmar Bergman’s “Cries and Whispers,” and it closed with William Friedkin’s “The Exorcist.” Both films are about the weather of the human soul, and no two films could be more different. Yet each in its own way forces us to look inside, to experience horror, to confront the reality of human suffering. The Bergman film is a humanist classic. The Friedkin film is an exploitation of the most fearsome resources of the cinema. That does not make it evil, but it does not make it noble, either.

The difference, maybe, is between great art and great craftsmanship. Bergman’s exploration of the lines of love and conflict within the family of a woman dying of cancer was a film that asked important questions about faith and death, and was not afraid to admit there might not be any answers. Friedkin’s film is about a twelve-year-old girl who either is suffering from a severe neurological disorder or perhaps has been possessed by an evil spirit. Friedkin has the answers; the problem is that we doubt he believes them.

We don’t necessarily believe them ourselves, but that hardly matters during the film’s two hours. If movies are, among other things, opportunities for escapism, then “The Exorcist” is one of the most powerful ever made. Our objections, our questions, occur in an intellectual context after the movie has ended. During the movie there are no reservations, but only experiences. We feel shock, horror, nausea, fear, and some small measure of dogged hope.

Rarely do movies affect us so deeply. The first time I saw “Cries and Whispers,” I found myself shrinking down in my seat, somehow trying to escape from the implications of Bergman’s story. “The Exorcist” also has that effect--but we’re not escaping from Friedkin’s implications, we’re shrinking back from the direct emotional experience he’s attacking us with. This movie doesn’t rest on the screen; it’s a frontal assault.

The story is well-known; it’s adapted, more or less faithfully, by William Peter Blatty from his own bestseller. Many of the technical and theological details in his book are accurate. Most accurate of all is the reluctance of his Jesuit hero, Father Karras, to encourage the ritual of exorcism: “To do that,” he says, “I’d have to send the girl back to the sixteenth century.” Modern medicine has replaced devils with paranoia and schizophrenia, he explains. Medicine may have, but the movie hasn’t. The last chapter of the novel never totally explained in detail the final events in the tortured girl’s bedroom, but the movie’s special effects in the closing scenes leave little doubt that an actual evil spirit was in that room, and that it transferred bodies. Is this fair? I guess so; in fiction the artist has poetic license.

It may be that the times we live in have prepared us for this movie. And Friedkin has admittedly given us a good one. I’ve always preferred a generic approach to film criticism; I ask myself how good a movie is of its type. “The Exorcist” is one of the best movies of its type ever made; it not only transcends the genre of terror, horror, and the supernatural, but it transcends such serious, ambitious efforts in the same direction as Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby.” Carl Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is a greater film--but, of course, not nearly so willing to exploit the ways film can manipulate feeling.

“The Exorcist” does that with a vengeance. The film is a triumph of special effects. Never for a moment--not when the little girl is possessed by the most disgusting of spirits, not when the bed is banging and the furniture flying and the vomit is welling out--are we less than convinced. The film contains brutal shocks, almost indescribable obscenities. That it received an R rating and not the X is stupefying.

The performances are in every way appropriate to this movie made this way. Ellen Burstyn, as the possessed girl’s mother, rings especially true; we feel her frustration when doctors and psychiatrists talk about lesions on the brain and she knows there’s something deeper, more terrible, going on. Linda Blair, as the little girl, has obviously been put through an ordeal in this role, and puts us through one. Jason Miller, as the young Jesuit, is tortured, doubting, intelligent.

And the casting of Max von Sydow as the older Jesuit exorcist was inevitable; he has been through so many religious and metaphysical crises in Bergman’s films that he almost seems to belong on a theological battlefield the way John Wayne belonged on a horse. There’s a striking image early in the film that has the craggy von Sydow facing an ancient, evil statue; the image doesn’t so much borrow from Bergman’s famous chess game between von Sydow and Death (in “The Seventh Seal”) as extend the conflict and raise the odds.

I am not sure exactly what reasons people will have for seeing this movie; surely enjoyment won’t be one, because what we get here aren’t the delicious chills of a Vincent Price thriller, but raw and painful experience. Are people so numb they need movies of this intensity in order to feel anything at all? It’s hard to say.

Even in the extremes of Friedkin’s vision there is still a feeling that this is, after all, cinematic escapism and not a confrontation with real life. There is a fine line to be drawn there, and “The Exorcist” finds it and stays a millimeter on this side.