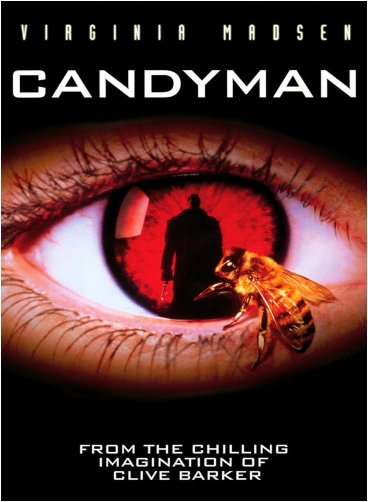

Candyman

Helen conducts a research on metropolitan folklore. While collecting interviews, she discovers that many people fear Candyman, a ruthless killer who, when summoned in front of the mirror, brutally kills the victims with a hook. During the continuation of the study, the legend seems to have a real foundation (dramatic murders that occurred in a popular neighborhood years before), a fact that scares and attracts Helen at the same time. But sometimes the boundaries between reality and fantasy, as between past and present, are fleeting: and the horror that Helen is studying will lead her to discover something new (and terrible) even about herself.

In this unfairly forgotten film, Bernard Rose proposes a terrible genius loci: in fact a popular area (Cabrini-Green) seems to be manned by Candyman, a bloodthirsty spirit that guts with a hook anyone who summons him in front of the mirror. Helen finds him out by chance, collecting interviews for her thesis on contemporary folklore.

After discovering that some years earlier, precisely in the Cabrini-Green, some violent homicides remained unpunished, Helen hypothesizes to have mistakenly collected only narratives, concerning real events that have been modified, year by year, by word of mouth. But when she begins to convince the interviewees that Candyman does not exist, the role of Helen is dramatically overturned from an observer to an (involuntary) accomplice to the crimes of the evil spirit. In fact, like any egregore, Candyman is "alive" as long as people believe in him. And this belief can be kept alive in one way only: by continuing to sow terror.

Bernard Rose develops the plot convincingly, thanks also to the skilful maintenance of Helen's point of view. We immediately sense her mysterious attraction to Candyman (and the way she is scared of it). We hold our breath with her when she finds out the truth about a man who was barbarously tortured and killed for loving the wrong woman. We cry with her when nightmares and reality merge incomprehensibly, and it is no longer possible to separate her destiny from that one of a hopeless monster who compulsively desires to carry out his original - and now horrific and unlikely – project.

Candyman's most brutal behaviors are "invisible" just like his ghastly name is "ineffable": splatter scenes lovers will perhaps be disappointed, but not being too explicit is a winning choice in last instance. And Philip Glass' melancholy soundtrack contributes to maintaining an engaging atmosphere, so that the film's increasing tension smoothly flows into a compelling finale.

At the same time, it is not easy to hold many other complex insights together. Perhaps this is why some good ideas (such as the passing of baton from pictorial art to graffiti, or the never resolved racial question) remain inadequately developed and risk appearing almost pleonastic, especially when the development of the main events must necessarily prevail.

However the film remains a good cinematographic transposition of Clive Barker's story, with Tony Todd's physique du rôle that makes the terrible ghost even creepier than in the original version, and a rightly awarded Virginia Madsen (with Saturn Award and other awards) for her performance as Helen Lyle . A film that deserves to be seen. In a room without mirrors, of course.