It Follows - The return of Bravura Horror

On the evening of Aug. 8, 1993, Showtime aired Body Bags, a 90-minute pilot for what the network hoped would become a long-running horror anthology series in the style of HBO’s Tales from the Crypt. (Needless to say, it did not.) The first instalment, “The Gas Station,” is directed by John Carpenter, and it is a short, perfect film, not a frame out of place across its swift 23 minutes.

Its premise is simple: a young college student, arriving at a small-town Illinois gas station for her first shift as its overnight attendant, finds herself beleaguered by a local mental asylum’s murderous escapee, thought to be lurking, of course, nearby. The story proceeds as you’d expect. What distinguishes “The Gas Station” is Carpenter’s style — his command of form. Sweat-inducing tracking shots, gasp-worthy closeups: on a rote slasher trifle Carpenter brought a kind of mastery to bear. The result is a spasm of virtuosity. It’s bravura horror.

Bravura horror: we don’t see much of that anymore. What do we see instead? Mid-range studio affairs dulled and flattened by a televisual aesthetic. Haunted-house cheapies whose highest formal aspiration is to make three million dollars look like 30. Or, more alarmingly, those ubiquitous “found footage” pictures, which have relinquished any pretence of style on purpose. Some of these films of have much else to recommend them. But few seem directed with any real sophistication — with what you’d have to call authorial vision. So when one that does emerges it’s only natural to find critics quick to celebrate.

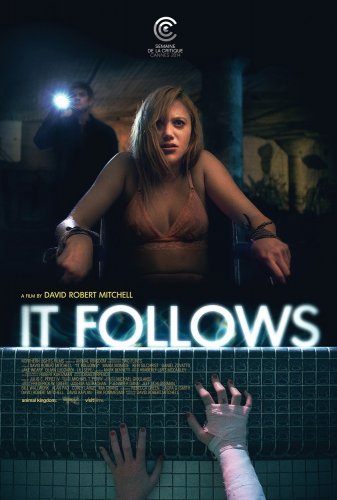

The new horror film It Follows opens theatrically this weekend, nearly a year after premiering to a great deal of acclaim at Cannes last May. Its director, David Robert Mitchell, has proven himself to be a virtuoso: a young auteur with a good eye and, with only two features to his name, an already highly developed style. Hardly surprising, then, that Mitchell has been widely compared to John Carpenter.

Mitchell’s formal command announces itself within seconds. Indeed, it’s made manifest in the opening shot: a striking long take that tracks a teenage girl’s retreat in fright from her suburban front door, a bit of old-fashioned, Halloween-like synthesizer throbbing ominously beneath it. The girl backs away down the smoothly paved road, her terrified eyes pinned wide, as an elder neighbor unloading groceries a few houses away asks if everything is alright. She says she’s fine. Minutes later she turns up dead: sprawled unnaturally in the soft dawn light on the shore of a beach, her left thigh snapped in half like a turkey bone.

This is not exactly panache on the order of The Shining, but it’s clearly the work of a director more interested in style than most. But why do so few excel in this manner? There are plenty of formally adventurous films inflected to some degree by a horror sensibility. Earlier this week, the website Criticwire polled writers about the best horror films of the past15 years, and the respondents trotted out the candidates you’d expect: David Lynch’s Inland Empire, Claire Denis’s Trouble Every Day, Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin. Bravura abounds here, certainly. But these aren’t quite horror films in the traditional sense.

We all know a real horror film when we see one. And the contemporary horror film, as rigidly codified as a classical Hollywood western, affords its practitioners ample opportunity to brandish their facility for filmmaking craft, much in the way that a standard invites the jazz musician to both hone and demonstrate her expertise. In fact it’s precisely because the horror film is so unvarying that the genre furnishes directors with so much creative freedom, counterintuitive though it may seem: the familiarity of convention opens in each new horror movie a margin in which style might flourish.